- Home

- Candace Owens

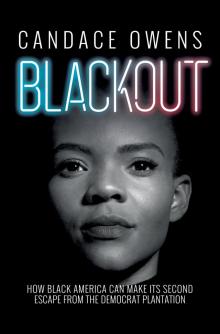

Blackout Page 7

Blackout Read online

Page 7

In April 2019, the school newspaper, the Williams Rec-ord, printed a full editorial board endorsement of the proposal:

We at the Record wholeheartedly support establishing affinity housing at the College. As a community, we must recognize that the College is a predominantly white institution in which students of color often feel tokenized, both in their residences and more broadly on campus. Establishing affinity housing will not single-handedly solve this problem, but it will assist in making the College a more welcoming, supportive and safe community for minoritized students.

Some say affinity housing reinforces division, arguing that having minoritized students cluster in one space would be harmful to the broader campus community. We believe, however, that allowing for a space where students can express their identities without fear of tokenization or marginalization will encourage students to exist more freely in the broader campus community, rather than recede from it.

The editor’s insinuation that supporting segregation was a matter of community safety very closely mirrors the same arguments made by Americans who were in support of the Jim Crow laws. Apparently, the broad characterization of policy decisions as necessary to community safety frees those who make such sweeping statements from any burden of having to prove their claims. Of course, there were no purported instances of black students’ at Williams College being physically harmed or otherwise threatened by the mere presence of white people.

While the efforts of campus segregation stand in extraordinarily stark contrast to the accomplishments made by six-year-old Ruby Bridges, I cannot feign surprise. I have witnessed firsthand what a disastrous state our college campuses are in; they are little more than social justice camps, coddling the minds of students through trained sensitivities.

It would certainly seem that America has come a long way since 1960—so far, in fact, that we may actually be returning to the place from whence we came. After decades of civil rights crusades, we have perhaps become so accustomed to fighting for progress that we are pushing it to the point of our own detriment. The truth is that black America currently finds itself in a position of privilege that civil rights leaders of the 1960s could only have dreamed. Yet rather than bask in the glory of our victories, we are instead creating new challenges.

All of these developments reflect the current social climate of America, which I have come to describe as “overcivilized.”

THE TREND TOWARD OVERCIVILIZATION

For all the strides we have made to get to where we are in American society today, progress did not arrive without extended periods of immorality—or periods of undercivilization. Human slavery, segregation, Japanese internment camps—these are all occurrences when civility was lacking and in desperate need of progressive reform. When called to we made the necessary changes to improve our society, and it is evident that our country’s worst days are far behind us. Unfortunately, not all nations can make the same claim. There are still live slave auctions in Libya, where migrants find themselves trafficked into forced labor and prostitution. And rather extraordinarily, in Malawi, albinos are kidnapped and sacrificed to witch doctors so that their body parts can be used for rituals designed to help politicians win their seats during general elections. Despite these horrific conditions, steps are being made toward progress; human trafficking and humanitarian aid groups are on the ground daily, working to improve the quality of life for people all over the world.

The desire and ability to progress over time is an inextricable part of our humanity. It is the reason that every civilization since the dawn of time has constantly sought improvement via innovation, scientific discovery, and philosophical debate. But what happens when civil maturity is realized, when basic rights and liberties have been ensured for all? What does a society strive toward then?

The answer is what I believe might be plaguing America today: overcivilization.

Civilization was achieved when we made the decision as a country to welcome law-abiding immigrants from around the world into our lands, while also providing due process for those seeking asylum from less civilized circumstances. But overcivilization is what is happening now via Democrat politicians’ demands that we become a country with no borders—allowing any and every undocumented person to flood into our lands.

Civilization was achieved for gay couples in the United States when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of same-sex marriage in 2015. Overcivilization, however, is the LGBTQ community’s current quest for transgender rights, or, more accurately described, the demand that biological men who self-identify as women be granted legal permission to use ladies’ restrooms and dominate women’s sports competitions.

We reached civilization within the black community when we received our rights to live, work, vote, and love in accordance with our own desires. Overcivilization is our current state of race-baiting, fabricated oppression, and calls for self-imposed segregation.

The absurdity of our circumstances has led me to contemplate whether peace might be an unnatural state for humanity. It’s why I often credit my generation, the millennials, for having turned our country into a whiny cesspool of neoliberalism. Let’s face it, those born in America after the 1980s are among the most privileged human beings ever to walk the face of the planet. And yet spending hours daily on our smartphones and rotating between various social media apps seems to have left us devoid of contentment. Our desire for a more meaningful existence has driven us to the never-ending pursuit of “social justice” causes: causes like gender-neutral bathroom signs, and proper pronouns available for those struggling with their identity. Indeed, only in a time of tremendous peace can such meaninglessness banter take place.

Our understanding of what it means to experience hardship has been warped by a prolonged period of goodness. The generation before us lived through the Vietnam War, which the United States combat forces participated in for seventeen grueling years. And just fourteen short years before the start of that conflict, young American men who should have been enrolling in college were instead enlisting in what would come to be known as the bloodiest conflict in human history: World War II. And just a little more than two decades before then marked the start of World War I, battles fought among men whose average age was twenty-four but reached as low as just twelve years. Fast-forward to today and students are demanding safe spaces on college campuses because they view it as a form of torture to be exposed to opposing viewpoints.

Yes, in the wake of achieving progress, in the manifestation phase of our ancestors’ dreams, we are now working overtime to dismantle all that they fought for.

We have no world wars to end, no major civil rights issues to champion, and yet our desire to triumph rages on. It would appear that we love an underdog story so much so that we are now unnecessarily casting ourselves as underdogs.

Of course, there is danger in this pursuit past the point of civilization. For it is possible to demand so much progress that regression is the natural result.

PLAYING THE RACE CARD—AND LOSING

When twelve-year-old Amari Allen claimed in September 2019 that three of her white male classmates at Immanuel Christian School in Springfield, Virginia, had pinned her down and forcefully cut her dreadlocks, the liberal community quickly gathered in a collective rage. “They were saying that I don’t deserve to live, that I shouldn’t have been born,” Allen said. She went on to explain in great detail how the boys held her hands behind her back and covered her mouth while they cut her hair with scissors, calling it “ugly” and “nappy.”

In the midst of a recent debate about black boys being excluded from sports for hairstyles deemed “inappropriate,” Allen’s story represented the icing on a perfectly baked media cake of white supremacy. It was tangible evidence that racism still permeates the lives of black children.

Left-wing networks immediately got behind the story. As a rule, they deem all stories of racial prejudice irresistible, but this particular story bore an unusual strand of novelty. As it would turn o

ut, Allen’s school was already familiar to the press. Familiar not only because it had made national news the previous January for a circulated parental agreement that stipulated that the administration reserves the right to expel students on the basis of promoting homosexual or bisexual activities (a typical guideline for religious schools)—but also because Immanuel Christian School employed Karen Pence, the art-teaching wife of Vice President Mike Pence. Naturally, every obsessed anti-Trump major media outlet, from CNN to CBS to the New York Times, was desperate to cover Allen’s hate crime. Reporters first castigated the school as a whole for allowing such a heinous crime to take place in the first place; they then moved to casting doubt on the credibility of a Christian education altogether; and then, of course, they used the Second Lady’s connection to the school to drive home their ultimate point, of a racist, bigoted Trump administration.

There was only one problem with Allen’s story, albeit a pretty big one: it never happened. As investigations into the attack got under way, security footage from the school revealed discrepancies in her initial account. When questioned about the inconsistencies, Allen finally admitted that she had fabricated the event.

The irresponsibility of her fabrication cannot be overstated. In her desire to be cast as a victim, Allen’s claim furthered the media-driven divide between black and white Americans, the former further convinced that they cannot live safely because of the color of their skin, the latter likely growing fatigued with another false-flag operation executed at their expense.

It was not so long ago that a fifteen-year-old girl named Tawana Brawley caused a similar fiasco, accusing four white men of raping her, tearing her clothes, writing racial slurs on her body, and smearing her with feces. The case stoked a media firestorm when the always-combative Al Sharpton began advising Brawley, fanning the flames of racial unrest. A number of black celebrities came out in support of the teenager: Bill Cosby offered a $25,000 reward for any information about the case, Don King pledged $100,000 toward her future education, and Mike Tyson gifted her with a watch valued at $30,000 to express his sympathy. Rather unfortunately for them, Brawley’s story didn’t check out. Soon after her attorneys dramatically named New York police officers and a prosecuting attorney as suspects, a grand jury determined that the attack was staged by Brawley herself, likely to avoid punishment from her stepfather for staying out past her curfew. “I had to sit down with my daughters and explain to them that this was a case where someone made reckless allegations,” accused attorney Steven Pagones told the New York Post in 2012. “It didn’t ruin me, but it certainly had a huge impact on every aspect of my life.”

Nearly twenty years later, in 2006, another scandal rocked the nation, when at the Duke University campus three members of the men’s lacrosse team were accused of rape. Crystal Gail Mangum, a black woman who attended a nearby university and worked part-time as a stripper, was hired to perform at an off-campus party hosted by the lacrosse team. Tensions between the team and the entertainment cut the party short, leading to Mangum’s early departure along with a woman who was hired to work the party with her. Soon after, the two women began arguing in a car, and when Mangum refused to exit the other woman’s vehicle, she was taken into police custody. Mangum was severely impaired, and while being involuntarily admitted to a mental health and substance-abuse facility, and while likely hoping to evade further trouble, she began spinning the tale of her rape.

The resulting fallout was tremendous. The alleged rape was deemed a hate crime. In early April, the team’s coach was forced to resign and Duke’s president canceled the remaining games of the 2006 season. Prosecutors soon learned that Mangum—who is now serving time in a Goldsboro, North Carolina, prison for an unrelated murder conviction—had been untruthful. In April 2007, all charges were dropped, declaring all three of the accused lacrosse players innocent.

But the social pollution from false allegations lingers long after the truth is revealed. In an article titled “The Cautionary Tale of Amari Allen,” Tom Ascol, the president of Founders Ministries, addressed the Allen controversy and what it said about the current state of our society:

We live in a hyper-racialized culture that undermines real racial harmony. Those who insist that every offense or slight that takes place as well as every inequity that exists between racially diverse people is necessarily due to racial injustice contribute to this combustible situation. All injustice is due to sin but not all injustice is due to sinful partiality. But when racism is redefined in terms of post-modern power structure formulas, then every failure of those impugned with “whiteness” is attributed to racial injustice.

To say that racial harmony is being undermined is an understatement. Our media pounces at every chance to cover discrimination because the Ghost of Racism Past has proven to be a profitable model. With money as their motive, I suspect they give little thought to what their negativity has inspired among the black youth. They must disregard entirely the fact that their fevered coverage is leading some to spin wild tales in a quest to live up to the hype of their own perceived oppression, while others experiment with self-imposed segregation. And in the process, the relationship between white and black Americans continues to fray, neither group benefiting from the resulting distance between each other. Despite the current trends and discussions, there is absolutely no proof that black Americans fare better at achieving, or are by any means safer among our own race. In fact, all evidence points to the contrary.

According to the 2018 Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups, nearly 60 percent of black students attend schools in which minorities constitute at least 75 percent of total enrollment.

Despite this, among fourth graders, the reading gap between white and black students was 26 points in 2017, and by the time black students enter high school, they are as far behind white students as they were twenty-five years earlier. In math, the gap between white and black students was 25 points in 2017. Black eighth graders were a full 32 points behind their white peers, another nearly identical statistic from decades earlier. When I think about these troubling statistics, I cannot help but think about Amari Allen and the wonderful opportunity she was given to attend an elite private school like Immanuel Christian, an opportunity most black girls her age are never afforded. And I can’t help but consider that despite the fact that her parents paid $12,000 per year to afford her that unique opportunity, she risked it all to lie about racism.

The idea that blacks fare better among other blacks is disproven not only by looking at our trailing academic performance, but also by the failure of most black inner-city neighborhoods; without question, our neighborhoods rank as the most unsafe in the country. The residents of the late Elijah Cummings’s district in Baltimore are certainly not benefiting simply because their community leaders are all black. Despite being represented by a black congressman, their neighborhood streets are littered with trash, empty buildings, and rodents scurrying between. The abandoned buildings, high crime rates, and plummeting home values paint a picture all too familiar to black communities that are run by black Democrats. Like Flint, Michigan, like Newark, New Jersey—communities run by left-wing politicians struggle to have even their most basic infrastructural needs met.

And while much hubbub has been created about the reasons that contribute to these circumstances, few dare point out the irony: liberal black Americans cry out often about the fear of white men, yet can claim no solace in predominately black spaces.

THE RACIST BOOGEYMAN

There is an endless stream of faux outrage, a constant manufacturing of nonexistent hurdles, rooted in some flawed concept of our society’s perfectibility. There are those in black America who use charges of racism as a social handicap. With the expectation that the mere utterance of the word will vindicate them in every scenario, we have arrived suddenly into an era of more insistence on rather than actual resistance against racism. And the Left, always happy to exploit our victimhood, urges us on. Many times, in fac

t, white liberals join in on the game, alleging that they see instances of discrimination and microaggressions everywhere, as proof of their commitment to our cause.

The personality complex of a liberal savior is one that fascinates me, as I believe it to be centered on extreme narcissism. I imagine them to be addicted to the feeling of accomplishment that is derived from helping someone inferior to them. I’d imagine it’s something like the feeling most get when they drop off items at Goodwill: a sense of charity, overridden by the more likely fact that they spend in excess of their needs. Standing up for inferior blacks must liberate liberals from having to assess their own flawed characters. Or perhaps, as in the case of Democrat politicians, they will simply say anything to garner our support.

While it is well within reason to remark at injustice, the immediate claim that every moment of our temporary discomfort is due to inherent racism is as insane as suggesting that the solution to such discomfort is segregation. It is impossible to forge ahead while walking backward.

And consider the drama if it were white people who made such recommendations, accusing blacks of racism and calling for separate (but equal!) dormitories to quarantine themselves from such offenses. We would be utterly outraged, so why is our response any different when members of our own community author such proposals? I have given consideration to the idea that recognizing our equality might make some black people uncomfortable, because with no one to blame but ourselves for failures, the weight of our own irresponsibility may seem too heavy a burden to bear. It is much easier to go through life with a white supremacist boogeyman.

Blackout

Blackout