- Home

- Candace Owens

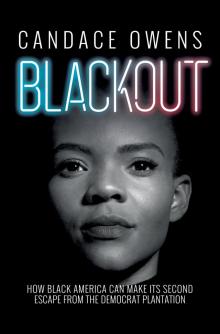

Blackout

Blackout Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Some names and identifying details have been changed.

To Grandma and Granddad.

May my every action make you proud.

FOREWORD

At a recent congressional hearing on the alleged rise of white nationalism, Candace Owens said the following:

I am hopeful that we will come to a point where we will actually have hearings about things that matter in America, things that are a threat to America, like illegal immigration, which is a threat to Black America, like socialism, which is a threat to every single American, and I hope that we see that day. It’s definitely not going to be today. Fortunately, we have Republicans that are fighting every single day, day in and day out.

For all of the Democrat colleagues that are hoping that this is going to work and that we’re going to have a fearful Black America at the polls, if you’re paying attention to this stuff that I’m paying attention to, the conversation is cracking, people are getting tired of this rhetoric, we’re being told by you guys to hate people based on the color of their skin or to be fearful. We want results. We want policies. We’re tired of rhetoric, and the numbers show that white supremacy and white nationalism is not a problem that is harming Black America. Let’s start talking about putting fathers back in the home.

Let’s start talking about God and religion and shrinking government, because government has destroyed Black American homes, and every single one of you know that. And I think many people should feel ashamed for what we have done and what Congress has turned into. It’s Days of Our Lives in here, and it’s embarrassing.

Mic drop.

Incandescent. Bright. Most of all, Owens is courageous. These are just some of the adjectives that describe this young, charismatic female who happens to be black and who happens to challenge the notion that blacks should retain their near-monolithic support for the Democrat Party.

In 2008, for the first time, the percentage of eligible black voters who voted exceeded the percentage of eligible white voters who voted. This shows, despite liberal rhetoric to the contrary, that the black vote is not being “suppressed” due to racism. Barack Obama actually got a higher percentage of the white vote than John Kerry did in 2004. Donald Trump, despite allegedly using a “dog whistle” to inspire white racist voters to turn out, received a smaller percentage of the white vote than Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney four years earlier. In 2016, Donald Trump received approximately 7 percent of the black vote.

Blacks have voted for the Democrat Party since Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal. Candace Owens dares ask, What have blacks gotten for their loyalty to the Democrat Party? Democrats preach and teach blacks to think and act like perpetual victims, eternally plagued by “institutional” or “structural” or “systemic” racism, never mind overwhelming evidence to the contrary. After all, this is a country that, in 2008, elected a black man for president, and in 2012, despite a tepid economy, reelected him.

CNN analyst Van Jones attributed Trump’s victory in 2016 to “whitelash.” On election night, Jones explained: “This was a whitelash against a changing country. It was whitelash against a black president in part. And that’s the part where the pain comes.” But where is the evidence? Of 700 counties that voted for Obama in 2008 and 2012, 200 switched to Trump in 2016. When were the white voters in those counties bitten by the racist radioactive spider? The city with more than 100,000 in population that voted most for Trump was Abilene, Texas. Yet this majority-white city, founded in 1881, recently overwhelmingly voted for its first black mayor.

The biggest problem in the black community is not racism, inequality, lack of access to health care, climate change, the alleged need for “commonsense gun control laws,” or any of number of the arguments Democrats pitch to blacks to secure that 90-percent-plus black vote. The number one problem in the black community, as Owens told Congress, is a lack of fathers in the home.

Economist Walter Williams points out that the percentage of blacks born outside of wedlock in 1940 was approximately 12 percent. In 1965, when Daniel Patrick Moynihan published a report called “The Negro Family: A Case For National Action,” the percentage of black children entering the world without a father in the house was at 25 percent. Moynihan warned about the dysfunction created by absentee fathers, including a greater likelihood of kids dropping out of school, an increased probability that kids would end up in poverty, and a greater likelihood that such children would commit crime and end up incarcerated. In a speech on Father’s Day in 2008, then-senator Barack Obama said: “We know that more than half of all black children live in single-parent households, a number that has doubled—doubled—since we were children. We know the statistics—that children who grow up without a father are five times more likely to live in poverty and commit crime; nine times more likely to drop out of schools, and twenty times more likely to end up in prison. They are more likely to have behavioral problems, or run away from home, or become teenage parents themselves. And the foundations of our community are weaker because of it.”

Today, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 70 percent of black children enter into the world without a father in the household. At the congressional hearing on white nationalism, Owens said, “If we’re going to have a hearing on white supremacy, we are assuming that the biggest victims of that are minority Americans. And presumably this hearing would be to stop that and preserve the lives of minority Americans. Which, based on the hierarchy of what’s impacting minority Americans, if I had to make a list of one hundred things, white nationalism would not make the list.”

Eric Holder, President Barack Obama’s first attorney general, denounced what he called “pernicious racism.” At a commencement speech before a historically black college, Holder said, “Nor does the greatest threat to equal opportunity any longer reside in overtly discriminatory statutes like the ‘separate but equal’ laws of sixty years ago. Since the era of Brown [v. Board of Education], laws making classifications based on race have been subjected to a legal standard known as ‘strict scrutiny.’ Almost invariably, these statutes, when tested, fail to pass constitutional muster. But there are policies that too easily escape such scrutiny because they have the appearance of being race-neutral. Their impacts, however, are anything but. This is the concern we must contend with today: policies that impede equal opportunity in fact, if not in form.”

Yet about the current state of anti-black racism in America, Holder’s future boss, then-senator Obama, said something different. In a speech at a historically black college, Obama saluted what he called the “Moses generation,” the generation of Martin Luther King. Obama said, “The Moses generation has gotten us 90 percent of the way there. It is up to my generation, the Joshua generation, to get us the additional 10 percent.” Again, this was before he was elected and reelected as the first black president of the United States. One can assume that Obama’s milestone election whittled down that remaining 10 percent.

In 1997, a Time/CNN poll asked black and white teens whether racism is a major problem in America. Not too surprisingly, a majority of both black and white teens said yes. But then black teens were asked whether racism was a “big problem,” a “small problem,” or “no problem at all” in their own daily lives. Eighty-nine pe

rcent of black teens said that racism was a small problem or no problem at all in their own daily lives. In fact, more black teens than white teens called “failure to take advantage of available opportunities” a bigger problem than racism.

Today, however bad-off someone black might be, whatever he or she is going through is nothing like the obstacle course black men and women dealt with two generations ago. For today’s generation of blacks to act as if their struggle compares to that of two generations ago insults and diminishes that generation’s struggle.

Reparations are the latest shiny object dangled to entice black voters. Several of the 2020 Democrat presidential candidates support establishing a commission to study it. But the problem is simple. Reparations are the extraction of money from people who were never slave owners to be given to people who were never slaves. It is revenge for something that was done to ancestors at the expense of people who had nothing to do with it.

Older black people went through a lot. Accordingly, they have understandable and well-deserved hard memories. It is within the living memory of blacks that endured Jim Crow. When I was born, Jackie Robinson had broken the modern baseball color barrier just a few years earlier. When I was born, interracial marriage was still illegal in several states.

But of the post–civil rights era blacks, the well-dressed tenured-professor types one sees on CNN and MSNBC, what was their struggle? Microaggressions? He or she was followed in a department store? Someone mistook him or her for a store clerk? Oh, the humanity!

The number one cause of preventable death for young white men is accidents, like car accidents. The number one cause of death, preventable and unpreventable, for young black men is homicide, and almost always at the hands of another black man. There are approximately 500,000 nonhomicide violent interracial felony crimes committed every year in recent years. According to the FBI, nearly 90 percent of the cases are black perpetrator/white victim, with just 10 percent white perpetrator/black victim. Where is the congressional hearing on this?

Dean Baquet, executive editor of the New York Times, once admitted: “The left, as a rule, does not want to hear thoughtful disagreement.” The black Left is worse. It does not feel thoughtful disagreement even exists. Owens, for example, was called, believe it or not, “a white supremacist”!

Where is the thoughtful discussion about the fact that nearly one-third of abortions are performed on black women; that illegal immigration disproportionately hurts unskilled blacks; that the welfare state has incentivized women to marry the government and men to abandon their financial and moral responsibility; that the demonization of the police causes them to pull back, resulting in an increase of crime, the victims of which are disproportionately black; the lack of choice in education especially harms urban blacks; and that programs like race-based preferences for college admission and the Community Reinvestment Act are hurting more than helping?

Recent polls show that blacks, thanks in part to people like Owens, are beginning to rethink their devotion to the Democrat Party. Some polls in late 2019 found black support for President Trump at more than 30 percent. Even an NAACP poll put black Trump approval at 21 percent, nearly three times the percentage of the black vote Trump received in 2016.

More than thirty years ago, Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson, a black Democrat, said, “The sociological truths are that America, while still flawed in its race relations… is now the least racist white-majority society in the world; has a better record of legal protection of minorities than any other society, white or black; offers more opportunities to a greater number of black persons than any other society, including all those of Africa.”

Carry on, Ms. Owens.

—Larry Elder, January 2020

INTRODUCTION WHAT DO YOU HAVE TO LOSE?

What does it mean today to be a black American? Does it even mean anything more than simply my skin color being black and my having been born in a landmass bordering the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans? Indeed, why does being a black Canadian, a black Russian, or just even a black person from southern Africa not carry quite the same weight as being a black American does? Why has my identity group been debated with more significance than those in other countries of the world?

If you are a black person in America today, your identity is as much defined by your skin color as it was more than a hundred years ago and quite similarly, for all the wrong reasons.

To be a black American means to have your life narrative predetermined: a routine of failure followed by alleged blamelessness due to perceived impotence. It means constant subjection to the bigotry of lowered expectations, a culture of pacifying our shortcomings through predisposition.

Above all else, being black in America today means to sit at the epicenter of the struggle for the soul of our nation, a vital struggle that will come to define the future of not only our community, but our country. A struggle between victimhood and victorhood, and which adoption will bring forth prosperity.

Will we decide upon victimhood? Will we choose to absolve ourselves of personal responsibility and simply accept welfare and handouts from the state? Or will we awaken ourselves to our potential through the recognition of our own culpability?

It is undeniable that for black America, the Democrats have had the upper hand for several decades. They have expertly manipulated our emotions, commanding the unquestionable commitment of our votes. Unlike the physical enslavement of our ancestors’ past, today the bondage is mental. Our compulsive voting patterns empower no one but the Democrat leaders themselves, yet we remain invested in their promise that welfarism, economic egalitarianism, and socialism will somehow render us freer.

Understand that it was not always like this. While blacks certainly have always generally voted in a bloc, that bloc did not always exist beneath the Democrat Party. In the beginning, of course, blacks were committed Republicans. When black men were given the right to vote in the 1870s, they cast their ballots on behalf of the party of their great emancipator, Abraham Lincoln. Post–Civil War Reconstruction efforts began strong—blacks were given land to work and federal protection courtesy of Union soldiers, and in short time went into business and were elected to political offices. But southern Democrats, still wallowing in their defeat from the Civil War, were outraged to see that the formerly enslaved were ascending in social status, and would soon avenge their grievances.

Buoyed by the 1865 assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the resultant presidential appointment of his vice president, Democrat Andrew Johnson, southern Democrats began efforts to reverse every Reconstructionist gain. White vigilante bands used physical force to keep blacks from voting, allowing for segregationists to be elected to Congress. With their political power affirmed, new regulations, which would come to be known as “Jim Crow laws,” were implemented. Stripping blacks of their newly gained sense of enfranchisement, these laws redesignated blacks as second-class citizens. Then came the Compromise of 1877: After a corrupted presidential election of 1876, Democrats agreed to concede to Republican candidate Rutherford Hayes—on the condition of his agreement to remove Union troops from the South. After the Civil War, Union troops were stationed throughout southern states to, among other things, safeguard the newfound rights of black Americans. The compromise left black Americans once again at the full mercy of racist whites, who were determined to be restored to their prewar lifestyles. Naturally, after so many demeaning blows delivered at the hands of Democrats, blacks remained fiercely loyal to the Republican Party. So when did this begin to change?

Fifty years later, when the nation was engulfed by the Great Depression, a Democrat’s promise of government programs that would lift every American out caught the attention of struggling black citizens. In March 1936, eight months before the presidential election pitting Franklin Delano Roosevelt against Republican Alf Landon, Kelly Miller of the Pittsburgh Courier (one of the most widely read black newspapers in the country) explained why he believed blacks should keep Roosevelt in the White House.

He wrote,

I am for the re-election of Roosevelt because his administration has done as much for the benefit of the Negro as could have humanly been expected under all of the handicapping circumstances with which he had to contend. There has been no hint or squint in the direction of hostile and unfriendly racial legislation. Scarcely a harsh denunciatory word has been heard in the Halls of Congress against the Negro, such as we had become accustomed to for a generation under both Democratic and Republican rule. Roosevelt has given the Negro larger recognition by way of appointive positions than any other administration, Democratic or Republican, since Theodore Roosevelt. In the administration of huge appropriations for work and relief, the Negro has shared according to his needs.…

While the New Deal was far from perfect and FDR stopped short of actively advocating for black civil rights, his efforts were deemed more substantive than his opposing Republican contender. Blacks saw a window of opportunity and they took it, with a decisive 71 percent of them casting their ballot on behalf of the Democrat nominee. Through the lens of their subhuman treatment and economic desperation, they felt that they had nothing to lose.

Then, thirty years later, Democrat president Lyndon B. Johnson signed both the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law, all but cementing his party’s stranglehold on the black vote for decades to come. It was a watershed moment in American history—a pledged breakthrough for the black community. At long last, blacks would be able to bid farewell to the days of oppression, and step fully inside the American dream.

Of course, no such thing happened, or else I would have no need to write this book. In reality, despite our faithful marriage to the Democrat Party, black America has made scarcely any improvement by way of closing the achievement gap with white Americans.

Blackout

Blackout