- Home

- Candace Owens

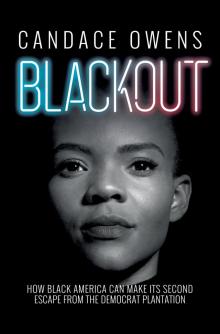

Blackout Page 3

Blackout Read online

Page 3

I laugh at the assertions. Foremost because even a most preliminary of online searches of me will reveal that long before I entered politics, I gave a TEDx talk titled “The Truth About Your Activism,” which was about the hate crime that I experienced. So much for trying to hide it! Ironically, it was exactly this experience from my childhood that sobered me to the reality of race, politics, and those who profit from the perpetuation of both.

The story begins one night in 2007, when I was curled up on a couch, watching a film, at my boyfriend’s home. Throughout the film, my cell phone kept ringing. Since my service was spotty, I chose to ignore the calls, and set my phone’s ringer to silent. In retrospect, it’s amazing to consider how that one innocuous decision would transform my life.

Later, when I returned home and my reception was restored, I noticed that there were four voice mails to match the missed calls. I thought it strange that the calls came through back-to-back, and that the anonymous caller decided to leave a message each time. Suddenly worried that there might have been an emergency, I listened to the voice mails:

Dirty N*gger… We’re gonna tar and feather your family. I’m gonna kill you, you know? Just because you’re f*cking poor. And you’re black. Okay? You better not be f**cking there, ’cus you might get a bullet in the back on your head. You big whore. You fucking whore… Martin Luther King had a dream. Look at that n*gger, he’s dead. That n*gger is dead! Harriet Tubman—that n*gger? She’s dead, too! Rosa Parks, that f*cking n*gger, she’s dead!

They went on and on.

It is difficult to land upon the correct adjectives to convey exactly what I felt when the messages had concluded, except to say that my reaction was physical. It was like having the wind knocked out of my chest—an unexpected force stealing my oxygen immediately. I was overwhelmed and suffocating all at once. The funny thing is that I can still feel it. When I think back to that moment in 2007, I recall every detail so vividly that it makes my heart ache. I ache for high school Candace, alone and crying, unaware of what the next morning would bring. High school Candace couldn’t possibly have known it, but the ugliness and hurt would be but a rough pathway to enlightenment.

But there is no portal to our pasts, only our careful retrospective observations, and what will always stun me about that night is the fact that I did nothing and told no one. I was immediately stunned into inaction. I felt fearful, shocked, embarrassed—and remarkably alone.

Call it an opinion, but I believe high school must rank chief among the most traumatizing years of any person’s life. It’s an awful period of teenage angst and uncertainty, compounded within a threatening timeline of life decisions to be made. Most students are trying to figure out where to fit in socially: what clothes to wear, whose lunch table to sit at, whether or not he/she likes you back. If I had within my possession a time machine that could bring me back to high school, I would set fire to the machine. Truly. The only thing that got me through those years was ego. I wore mine every day like an armor to mask every plausible point of vulnerability. The morning after I received the messages, I felt as though I was dying on the inside, but through the lens of teenage vanity, the inside isn’t what counts. And on the outside, I was my usual faux-confident self. I exhibited no signs that I had cried through the night. My first-period class was “Senior Seminar.” It was a philosophy course where my teacher encouraged open discussion and debate about politics, current events, and the fallacies that lay between. The style of the class was open forum. I think for many of us, the course became a form of necessary therapy—a rescue from the mounting external pressures that threatened to combust us all. I don’t recall what the topic of the day was or what prompted me to raise my hand and volunteer a response to it—but volunteer I did. I can’t tell you what response I was looking for in that moment and from that classroom filled with pupils, but I shared it all. Maybe I was just feeling bad for myself. Maybe I wanted to shock them in the way that I had been shocked. Maybe I was looking for sympathy or some general consensus that the world was irrevocably broken, but I made the decision to share it all. And the chain of events that it set off was something that I could have never predicted. In a responsive moment of absolute authority, my teacher commanded me to “get up” and follow him to the principal’s office. Upon hearing the voicemail messages, she immediately phoned the police. And my entire life transformed thereafter.

It would turn out that the perpetrators were a group of boys led by my former friend Zack. Zack was upset that I had started a relationship with my boyfriend and had less time for him, so when he and his three friends (whom I had never so much as met) found themselves bored and under the influence one night, prank-calling me seemed to be a perfectly reasonable way to pass the time. Incidentally, one of Zack’s friends happened to be the fourteen-year-old son of our city’s mayor (and the future Democrat governor of Connecticut), Dannel Malloy.

For the media, the political connection proved irresistible.

Within days, my face was splattered across the front page of every newspaper across the state, and I was a repeat story on the evening news. They played the voice mails ad nauseam. Since none of the boys would formally admit to their role, and because a politician’s son was involved, the police brought in the FBI to help analyze the voice mails.

My town was divided by the sensationalism. It felt as though every single person, teacher, student, and parent alike had entered in a social verdict. There were some people who were convinced I was lying. Since Zack was adamantly and boldly declaring to our classmates that he took no part in it, some began to invest in the Machiavellian narrative that I had phoned myself. More innocently, others believed that I was simply accusing the wrong guy.

As the leading bastion of progressivism and civil rights, the NAACP were more than happy to insert themselves into the narrative. They beelined to the front steps of my high school, where they greeted news cameras anxious to receive statements pertaining to the injustices of the investigation. To their credit, they rightfully called out the unusual delay of justice that was more than likely tied to the case’s political angle. Administrators from my school were protecting the perpetrators because of the mayor’s son, and the NAACP took them to task. What the NAACP did not do, however, was ever actually speak to me. I never had an interview or a meeting with any of my so-called allies who were so eager to speak out about racism but not interested in me, the real person at the center of the story.

It took six weeks before the FBI investigation concluded, before the articles stopped being written, before the opinion letters to the editors stopped accompanying every newspaper, and before my name was officially cleared as a co-conspirator in my own case. As it turned out, I had not phoned myself. Subsequently, arrests were made and charges were brought. I was labeled, officially, as the victim. And then everybody disappeared. Everybody but me, of course. I was left to deal with the emotional roller coaster of sudden, unwanted infamy and controversy, followed by utter desertion.

If this narrative sounds familiar to you, it may be because it has become part and parcel of our mainstream media agenda. A school shooting takes place, only to have the survivors hijacked by gun control activists looking to jam through their policies in a time of high emotion. A black man is killed by a police officer, and his image is used to further the narrative that white cops are murdering black men for sport.

Over and over again, somebody else’s real pain and tragedy are reduced to media talking points to further a political agenda. Emotions are elicited and concern is feigned until a bigger story comes around.

This soured my perspective on the world early in life. Fundamentally, I began to believe that the world was happening to me, that I was a tragic Shakespearean figure doomed to fail because of the unfortunate circumstances of my childhood. This quite naturally led me down a path of liberating myself from any concept of personal responsibility. I drank, I partied, I got into fights. Everywhere in my life I created chaos because chaos came to falsely repr

esent a state of freedom. I felt freed from rules, freed from regulations, freed from any accountability. And because I felt that my life’s narrative had been decided for me, I turned to anorexia to reassert control. For four years, I restricted how many calories I consumed. The lighter I felt I could make myself physically, the lighter I felt mentally. I felt freed from the weight of my past.

But with time, what was supposed to feel like freedom began to feel like bondage. I was pretending that a life with no rules made me feel freer, when in reality it made me feel insecure. I was losing more than pounds. I was losing myself.

This was leftism unleashed.

HARVESTING CONSERVATIVE SEEDS

There is a Bible proverb that reads “Train up a child in the way he should go, And when he is old, he will not depart from it.”

In early 2013, I got a call that my grandmother was sick. By this time, my grandparents had moved back to Fayetteville, North Carolina. In their retirement they purchased property and built their dream home upon a plot of land that my grandfather knew well; it was the sharecropping farm that he grew up on.

We were told that my grandmother would be out of the hospital by the end of the week. I packed a bag and traveled from New York to Fayetteville to visit her anyway—and I wasn’t the only one. As a symbol of her matriarchy, everyone got on a plane: cousins, brothers, sisters, and aunts. For the woman who had given us her all, we knew we needed to show up. The doctors insisted that she would be released in two days. As it turned out, she would be dead in two weeks. Unaware that it was the last time I would see her, I spent most of my time bragging to her about my fancy new job in New York City. In retrospect, I think my grandmother knew somehow—she knew the doctors had missed something and that she would never return home. She took care to speak to each of us in such a way that she hadn’t before.

When my grandmother turned her attention to me, I exuded my practiced confidence. I showed her an expensive new designer bag I had just purchased and told her all about my new job in private equity. I thought she would be proud of me, proud of how successful I was becoming. I thought wrong.

My grandmother, as she always did, saw right through the facade. “Candace,” she began, “I worry about you in New York. I feel like you are losing yourself.” I told her I was fine and not to worry. Believing that she would indeed be discharged in forty-eight hours, I bid her farewell and told her I would call her in a few days. That was the last conversation I ever had with her. She died ten days later, a shock and blow to my family that is still felt today.

Grief consumed me. Guilt consumed me. And while the grief was foreign, I knew the guilt well. Because there had been a quiet voice that had been with me since that high school hate crime, one that I chose to muffle, over and over again, from the back of my mind. That voice, gentle as it were, was unrelenting. It was patient, it was kind, but it was unrelenting, and the question was always the same:

Are you yet ready to set down the weight of victimhood? Are you ready to run this race of life, truly free?

And suddenly I was ready. I was ready to become how my grandparents had raised me. I replayed my grandmother’s last words in my head. She was right, I was losing myself. I recognized that my current worldview was not serving me. I needed to change my perspective, and I started by asking myself a simple question:

What if the world is not happening to Candace Owens? What if Candace Owens is happening to the world?

It was a daunting question. It implied that nothing was owed to me and that even those situations that were not necessarily my fault were, in the end, certainly going to be my problems to contend with. I embarked on a personal audit of my life that brought me to a deeper consideration of my grandparents’ sacrifices. While my grandfather was growing up on a sharecropping farm, drying tobacco, my grandmother was living in the Virgin Islands, unwanted because she was considered crippled. At just ten years old, she spent a full year of her life hospitalized after a surgery to correct her hips. I had never known my grandmother to walk without a limp. She lived in a constant state of physical pain. But never once had she or my grandfather ever complained. They did not complain as children, nor did they complain as adults, not even as they were forced to contend with the world’s problems in addition to their own. Yet there I was, with a full-fledged victim mentality, upset that life hadn’t been fair to me. It was pathetic.

I knew it was time. It was time to return to the only values and principles that had ever made me feel truly content.

The first principle was to refuse the victim narrative. If my grandfather could reduce the Klansmen to “boys,” surely I was capable of reassessing my own points of victimhood.

And so I mentally revisited the high school hate crime. In retrospect, I found it interesting to consider that in today’s society, we have developed something of an obsession with determining a victim and a villain, and then closing the door on any further analysis. Maybe we ought to blame Disney movies—our earliest point of indoctrination that there needs to be a hero and a bad guy in every story line. The hero wins, the villain loses, and the credits role. Off-screen, journalists have taken on the responsibility of passing judgment within the confines of absolute goodness or badness. Such blanket assessments have proven to be a profitable model, because sensationalism and hyperbole sell. Of course, humanity is much more complex than we’d like to believe. If the media had any nerve to dig beyond “racist white boys” phone “victim black girl,” they may have accidentally landed upon a much more human narrative.

As I mentioned earlier, Zack (who was dubbed by the media as the “ringleader” of the attack) was my former friend. That fact alone, under even amateur analysis, should have served as a clue that his actions were not inspired by deeply held racist views. Prior to the voice mails, Zack and I had spent nearly every day together over the course of a school year doing what high schoolers do: eating junk food, talking about dreams, unloading our anxieties. Then rather abruptly, I got a boyfriend and all of that ended. I became every bit the stereotype of a young teenage girl in love; I stopped hanging out with my friends, and my every second became about my new relationship.

If all of this sounds remarkably immature, it’s because it was. It was textbook, meaningless high school drama that led to a series of irreversible events. It is likely that after losing someone whom he trusted and confided in daily, Zack was hurt. It is likely that under the influence of alcohol, that hurt morphed into anger and in a moment of childish impulse and stupidity, he thought, “What can I say to make Candace hurt in the way that I am in hurting?” It is likely that in thinking of the most hurtful and hateful things he could possibly say to make me hurt, he chose racial slurs. People don’t like to hear that assessment because it’s too human. It doesn’t feed the media beast. It doesn’t quench our insatiable thirst to quickly identify evil and socially cancel the evildoer. I sometimes wonder if we so often seek to point out ugliness as a cheap formulaic way to convince ourselves that we are good.

Look what that bad person did. I would never do that. Therefore, I am good.

The resulting truth is that the media’s surface analysis of that night destroyed five lives: the four young boys, who were publicly stained as racists before they began their lives, and me, who was publicly labeled a victim before I had begun mine.

I knew what Zack did that night was wrong, and I had no doubt that his actions deserved consequence. But now, in a return to my conservative principles, I was wondering whether there was any permanence to his wrongful action, or to my victimhood. Could I evolve? Could he evolve? And who are those who insist that we ought not to?

RETURNING TO OUR CONSERVATIVE ROOTS

The glorification of victimhood is exclusively promoted by the Left. It becomes necessary that I first define exactly what I mean when I refer to “leftists” and “liberals” throughout this book and why I will, at many times, use their identities interchangeably.

Liberalism is defined as a political philosophy based o

n liberty and equality before the law. It is an allegiance to a set of principles that guarantee those who follow them, a society with more individual freedoms. True liberalism pursues principles like the right to life, right to vote, freedom of speech, etc. (When our forefathers wrote “Right to life,” liberty, and the pursuit of happiness they meant a right to life—literally). On behalf of black America, I will make an argument that liberalism has only ever been practiced by conservatives in this country.

Leftism is defined as any political philosophy that seeks to infringe upon individual liberties in its demand for a higher moral good. Leftists concern themselves not with principle, but with some greater morality that must be achieved. The issue with leftism is that moral goodness is, of course, subjective. Not so long ago, white supremacy was deemed the higher moral good, and in its pursuit, leftists infringed upon the rights of black Americans. Today, economic equality is the established higher moral good the Left is after, and we will soon unpack just how many liberties have been arrested in its pursuit.

So why are we seeing resurgent conservatism throughout Western societies? Because self-described “liberals,” those who like to view themselves as centrists are realizing that the hallowed middle ground of politics has been consumed by leftism. Leftists have been able to operate under the guise of liberalism, by claiming to want a certain type of equality. But demanding economic equality can be accomplished only by infringing upon individual liberties. The nuance here is important. Both liberals and leftists find themselves allied by the concept of equality, and an inability to recognize that their goals stand in radical opposition to one another. In essence, there is nothing more illiberal than leftism. And although many liberals have awoken themselves to this impossible partnership, others remain unable to achieve such clarity.

Blackout

Blackout